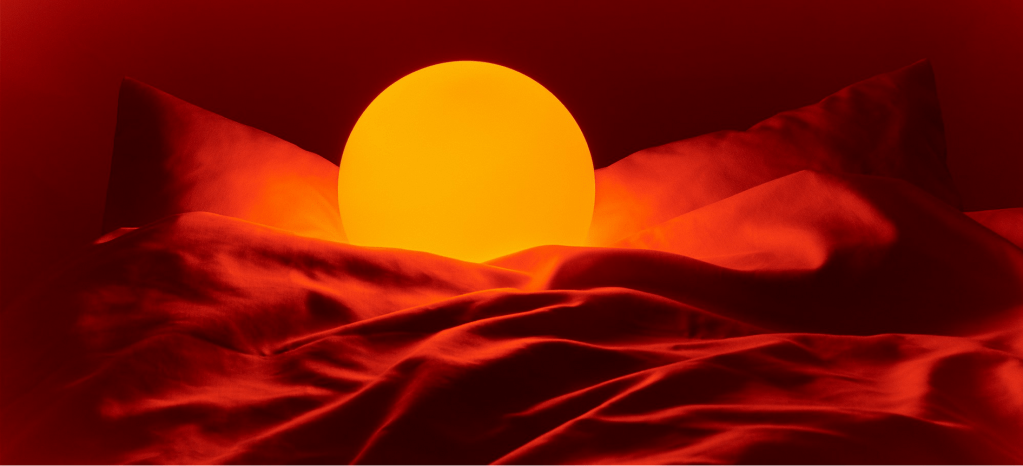

Being sleepless makes you just as cognitively impaired as being drunk. And as we get older, our sleep worsens. Here, two experts break down why that’s the case and what they’re doing to better understand sleep’s effects on the aging brain, and vice versa.

Sleep, the brain, and your health are a vexing trio. Up until the end of the 20th century, most researchers studying sleep and the brain were doing so simply to maximize human efficiency while minimizing sleepiness. Then in the late 1990s, a series of studies related to sleep and metabolism as well as circadian rhythm and its impact across the entire body blew the lid off the connections between our complex body systems and sleep. “We’ve learned so much in the past few decades,” said Kenneth Wright, Jr., Ph.D., a researcher at the University of Colorado Boulder who heads the Sleep and Chronobiology Laboratory there. “When I was graduate student, no one was talking about sleep and health.”

For the past few decades, researchers have been laser-focused on parsing out the huge role sleep and your brain plays in overall health — particularly as you age.

Yet, reaching inside the human brain to see what’s happening as people age, and why, remains a difficult task. People who have been studying these topics for their whole lives sometimes preface anything they’re about to say with a common disclaimer: We really don’t know that much about…

Here’s what we do know. Sleep is vital to your health. A 2010 analysis of sleep duration and all-cause mortality showed that both not getting enough sleep and getting too much increase your risk of death.

“We’ve learned so much in the past few decades. When I was graduate student, no one was talking about sleep and health.”

We know, too, that the connection between the brain and sleep is an important two-way street: Sleep affects the brain, and the brain affects sleep. We know that both change as you get older. Which is to say, that as you age, your sleep, and your brain, are going to change. That’s going to have dire impacts on your health.

That sounds like a lot of knowledge — and it is. And there’s a lot more the non-scientist can and should know about sleep and their brain as they get older. Here are the basics you should know.

What Happens to Your Brain as You Age?

Let’s lead with some disheartening news: If you’re approaching 40, your brain is shrinking and will continue to do so until you die. Studies have found that the brain of a healthy adult loses about 5 percent of its mass per decade beginning around age 40 (some experts say earlier); the shrinking may increase in speed after age 70. Scientists aren’t exactly sure why this shrinkage happens. But nearly all agree that certain areas, including the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex, which deal in memory and problem solving, perspectively, lose more mass than others.

Shrinkage is the most lurid example of aging’s effect on the brain. But the truth is, a lot of different changes happen to your brain as you age. Simply put, things start working as they shouldn’t, or don’t work as well, or stop working altogether. For instance, areas of the brain that communicate well in a young brain might begin to be disrupted or altered. Lines of communication between areas of the brain that hadn’t “talked” before might open up. This, again, is natural, and often, older adults’ brains are able to adapt cognitively. “The brain can undergo a lot of change — and you look at the person and they’re fine,” said Audrey Duarte, Ph.D., who heads the Memory and Aging Lab at Georgia Institute of Technology.

As you age, your brain is also changing on a more micro level. You were likely taught in grade school that the workhorse cells of the brain, neurons, cannot regenerate and die off en masse as you get older. That’s not entirely true — new evidence shows that neurons can sometimes regenerate and that neurogenesis, or the creation of new neurons, happens even in older people. But as adults approach 65, many neurons are damaged and function less rigorously in the aging brain, slowing and halting communication lines that ran like a high-speed rail in the younger brain: quick and on time. Neurotransmitters, too — hormones like dopamine, serotonin, and others that help neurons communicate chemically rather than through electric charges — are produced less and less as the brain grows older.

“The brain can undergo a lot of change — and you look at the person and they’re fine.”

The result of all this decay is, in the best case scenario, a path of slow cognitive decline. And yet, as Duarte noted, an old but healthy brain continues to function relatively well. The brain’s ability to adapt to these declines in order to maintain day-to-day cognitive function is called “plasticity.” But one area of decline is almost a constant: As we get older, we sleep less. Scientists believe this has a direct connection to the aging brain.

Unlocking Why We Sleep — and Sleep’s Connection to Aging and the Brain

From the veil surrounding the mystery of sleep, researchers have snatched a series of facts proving that it’s one of the most important times for the body as a whole. “Almost every system in the body — the immune system, hormones, the vascular system, etcetera — are impacted in one way or another by sleep,” Wright said.

A leading theory on why we sleep has to do with energy conservation. The idea goes that our bodies need to prepare for the following day: repair damage to cells and tissues, replenish hormones and neurotransmitters, and maintain important protection mechanisms like the immune system. We reduce our energy usage when we sleep, and, Wright said, this “allows us to take energy that we’ve saved and apply it to these other things. Sleep provides a time when those types of processes can occur effectively. Evolution probably utilized that time of sleep to make certain things occur most favorably.” In a recent study, researchers watched DNA repair mechanisms within the chromosomes of zebrafish embryos, which are translucent, and noted that certain chromosome dynamics associated with DNA repair increased in neurons during sleep, and were prevented during sleep deprivation.

“Almost every system in the body — the immune system, hormones, the vascular system, etcetera — are impacted in one way or another by sleep.”

This is all controlled by the brain, which promotes either wakefulness or sleep states — during the former, the frequent firing of neurons and release of neurotransmitters, and during the latter, a slowing of neuron firing associated with slow-wave brain activity. It’s thought that these mechanisms are controlled in a larger sense by circadian rhythm, a 24-hour “master clock” located in the hypothalamus.

Sleeping has been closely tied to our cognitive health: We know that being sleepless makes you just as impaired, cognitively, as being drunk. We also think that memory is tied to sleep. Specifically, many studies have linked memory consolidation and sleep. In a recent study, scientists including Duarte measured brain wave patterns of activity and memory creation in people while they were awake, and then measured the same brain wave patterns and activity while the same patients slept. The same patterns repeat during sleep. This “replay” or “reactivation” may be important, Duarte said, for “laying down that memory, making it stick.”

Given its importance to our health, sleep does something alarming as we age: It worsens. In particular, a measure called “sleepfulness after sleep” decreases — a fancy way of saying older people might be able to nod off in front of the TV easier than the rest of us, but that the sleep that follows is more interrupted, less “deep,” and generally shorter in duration than the young. A common estimate says that between 40 and 70 percent of older adults experience chronic sleep problems. There are a number of thoughts on why that’s the case. It could be that the body’s natural drive for sleep is not as strong as we grow older; it could also be that the drive remains just as hungry for sleep, but our body’s ability to respond to that drive is reduced.

Either way, a lack of quality sleep can cause a vicious cycle in the elderly: Lack of sleep begets impaired brain processes and impaired brain processes beget lack of sleep. This is true in common diseases of aging like dementia and Alzheimer’s, but it can also be simpler. An example: Pain from sore joints and muscles might keep your grandmother up at night; not sleeping enough doesn’t allow her brain to help her body heal those aches and pains through hormones and a robust immune system response. Your grandmother is not just tired, the health of her brain and therefore her body is suffering from the effects of aging.

How Can We Better Understand Sleep’s Effect on the Aging Brain, and Vice Versa?

For many scientists, the path to healthy sleep as we age, and therefore healthy brains, is more knowledge, along with reliable, non-invasive measures of what healthy sleep actually looks like.

Take one of the most important advances in studying Alzheimer’s disease and dementia in the past decade: measuring beta-amyloid protein plaques in the brain. Scientists have suggested a connection between these plaques, which are a protein “waste” from neuronal activity, and Alzheimer’s for several years. A study in 2018 showed a definite connection between lack of sleep and an increase in beta-amyloid proteins, which increased five percent after a sleepless night. Some scientists believe that the brain is cleared of these plaques during sleep; while there is currently no causal connection between beta-amyloid and Alzheimer’s disease, their presence is a hallmark of the disease.

At Wright’s lab, the focus is on biomarkers of sleep. “Currently, you can go to the doctor’s office and get a simple blood test to check for liver or thyroid problems,” he said. That’s not the case with sleep. Using metabolomics — the study of all the metabolites in the body — or proteomics — the study of all the proteins in the body — are high on the list of techniques. Surprisingly, so is studying the microbiome — all of the microorganisms that live inside us and have an outsized effect on our health. Since 2016, Wright and other researchers have been studying how the microbiome is affected by sleep deprivation and circadian rhythm issues.

At Duarte’s lab, she and her team are collaborating with researchers at Emory University to test a new way to measure beta-amyloid protein buildup in the brain without a painful spinal tap procedure. Using electrodes, they can measure a sleeping patient’s brain wave oscillations. Certain slow wave oscillations have been associated with brain pathologies including beta-amyloid protein buildup. By measuring a patient against normal brain wave activity, she hopes they can predict plaque buildup, and, therefore, risk for Alzheimer’s disease.

The idea is to better identify not just what’s going wrong in older people’s brains related to sleep, but what’s going right. “I see people come into my lab who are 75, and they just kill it on all these tests we give them,” Duarte said. “I think, ‘that’s amazing.’ I think, ‘How do I get like that?’”

All Rights Reserved for Elysium Health