We have forgotten more than we will ever know.

Places, names, faces, dates, relationships, experiences, causes for praise and blame, dance moves, math formulas, music scales, foreign words, niche words in languages we’d claim as our own — details of which, perhaps the very existence of which, have all faded from us like vapor against a warming sun.

Sometimes, they return like a drop falling back from the sky, summoned by a surprise association. Sometimes, they are simply gone.

This is the tragedy of our fallible memories. Even when we feel that we remember something exactly, odds are good that distortions have entered in. (Hence the low reliability of eyewitness testimony for courtrooms.)

One of the many promises of technology is to correct this fallibility — like a prosthetic mind.

Can’t quite remember some fact about world history? Just punch it into Google (or, if you care about privacy, DuckDuckGo). Want to remember someone’s birthday? Either store it in your phone or, better yet, just let Facebook alert you. If you’ve ever been annoyed at how some people always seem to pull out their phones to photograph or video every moment with the least bit of significance, you could see this too as a yearning for tech-assisted memory. People have even dreamed of an implantable “brain-Internet interface” that could make this memory work as seamless as possible.

But we should ask ourselves whether this cure is worse than the disease.

Just after the first iPhone was brought to market, Nicholas Carr warned of how constant Internet use can make our minds less acute. Then there was a much-cited psychology study in 2011 that showed that when we learn things on computers, we don’t remember the information so much as where we found it. As an extension of this finding, others have worried that we attend less to our everyday experiences when we anticipate them being recorded, creating a drag not just on memory but presence itself.

These writers take the thinking a long way, but not quite far enough. The question of whether we should rely on tech for much of our remembering is not simply about whether it can be more effective than our brains. It’s about the risk of losing track of an entire form of memory that’s central to the pursuit of a good life.

Two kinds of memory

We could benefit from a bit more precision with the term “memory.” I’d like to suggest that we distinguish here between two kinds — what I’ll call archival and formative memory.

To appreciate the difference, consider a moment from one of Plato’s dialogues.

Toward the end of Phaedrus (lines 274b-277a if you’d like to follow along), Plato’s character Socrates spins a tall tale: Once upon a time, there was an Egyptian deity named Theuth who tried to convince an Egyptian King named Thamus that he had found a magic potion for wisdom and memory.

The potion was writing. Intrigued but altogether unconvinced, Thamus retorted that writing could be a potion for reminding but not for remembering. Those who rely on writing, he says, would develop flabby memories and ultimately become forgetful. The problem with writing, Socrates adds, is how it relies on external signs. Far preferable is to have the object of memory written into your soul.

People sometimes cite this moment in Plato as a way of discrediting complaints about technology’s impact on memory. The Internet is just the latest in a long line of technophobic worries going all the way back to writing itself. Since it’s obviously crazy to worry that writing causes forgetfulness (so the dismissal goes), we ought not to worry about other technologies either.

That reasoning is hardly airtight, but more importantly, it misses the point. Plato isn’t worried about forgetfulness so much as the externalization of memory. When that happens, memory is reduced to reminders.

Archival memory

What Plato characterizes as “reminders” is a species of what I’m calling archival memory.

It’s a way of assembling the many and varied things that we consider important to recall occasionally but may lose without assistance. Archival memory involves (1) some kind of external capture and storage, combined with (2) a ready means of recall.

The National Archives (UK). Wikimedia Commons.

The archives you find in large research libraries are a paradigmatic example of this — hence the name. But we could see archival memory all around us: from low-tech things like the journal you kept in grade school to higher-tech things like the cloud, Wikipedia, or your phone’s reminder app.

Everyone relies on archival memory to some extent. The amount of stuff we have to remember is far too great to hold it all in mind. And many things simply aren’t important enough — beyond the opportunity to win at trivia night — to bother trying to remember if we can store them externally and retrieve as needed.

For the purposes of everyday archival memory, it’s hard to beat the technology available in a smart phone and some kind of internet connection. Used well, it can be faster, more accurate, and more comprehensive than more manual forms of archival memory. (I personally would be lost without my phone’s reminders and notes app.)

Formative memory

But formative memory, what Plato likens to writing onto your soul, is another matter entirely.

As the name implies, it’s about who we are and who we’re becoming.

There are some things we remember — the stats of a favorite baseball team, say — that may be important to us but make little difference in who we are. Whether you track the batting average of the Red Sox or Yankees likely will not make you a different person one way or the other. (As a Sox fan, that statement requires a lot of restraint, believe me.) But some things we remember make a tremendous difference in who we are. Favorite authors are one example. Whether you make a practice of memorizing quotes by, say, Immanuel Kant or Emily Dickinson or Bill O’Reilly could give you fundamentally different outlooks on the world.

The idea of memorizing quotes, however, could be misleading if we’re not careful. Often, we think of memory as an act of recalling something into consciousness, like a shiny object pulled from the recesses of a dark closet. But formative memory is less about explicitly recalling discrete bits of information than about our practical disposition in the world. It’s in the neighborhood of what psychologists sometimes call “implicit memory” — the kind at work, for instance, when you surprise yourself on a walk alone in noticing a particular shade-loving flower that your beloved used to have to point out for you.

We might develop this kind of memory through reading certain authors and internalizing what we read, but just as often, it comes through relationships.

Here’s the crucial point: Technology — whether we’re talking about your phone, the cloud, eerily omniscient AI, implants in your brain, or whatever — cannot and never will do the work of formative memory for us. Its memory work is inherently archival.

One might disagree by arguing that technology, like other forms of archival memory, can help to facilitate formative memory. After all, formative memory often relies on making information present to us. But the extent to which formative memory develops from this would be a function of how we use the technology, not something inherent about the technology itself.

At the end of the day, formative memory develops through the hard work of giving things our attention — a practice for which there is no shortcut, no “hack.”

The danger of fixating on technology in our conversations about memory is that we could lose all appreciation for the value of this attention and the kind of memory it cultivates. For in a paradigm of technology — a paradigm in which our brains are simply imperfect hard drives — we can only ever think in terms of archival memory. That would be a problem because there are ways in which formative memory is core to realizing our potential and living well as human beings.

What formative memory does for us

There are three things that strike me as especially important about formative memory. They’re distinguishable from each other, though deeply interconnected.

Constructive forgetting

It might seem odd for me to go on and on about memory and then highlight forgetting as a benefit. But let me explain. As I noted already, we can sometimes feel overwhelmed with the amount of stuff that we could, perhaps even should, remember. And as anyone who has taken a few too many photos or saved a few too many files to their desktop might attest, there are ways in which archival memory can be just as overwhelming.

The concern is no longer about losing things. It’s about losing track of them — or losing the signal amid the noise.

Scene from Black Mirror, “The Entire History of You”

This problem could get even darker. In an episode of Black Mirror called “The Entire History of You,” we witness an alternative reality in which almost everyone has an implanted “grain” that allows them to record every experience through their eyes. People can then play back their experiences for themselves and others. You could say that this world has brought archival memory to its utmost perfection. As you might imagine (though I’ll avoid a spoiler), this perfection causes trouble for people in intimate relationships, because they have trouble moving on from the past.

What happens in formative memory isn’t about forgetting as such. It’s about incorporating things from our past into who we are now, which necessarily involves focusing on some things — ideally, the most important ones — to the exclusion of others.

The Black Mirror episode is so poignant because intimate relationships require this kind of process if they are to last. Every relationship has its ups and downs. If the good things hold the deeper truth (though they don’t always), constructive forgetting allows us to hold onto them while relinquishing the bad over time.

To be sure, this process is not good in every case.

Some bad things in the past are so heinous that they should never be forgotten, at least on a societal level. For individuals who have been traumatized by them, forgetting, to whatever extent possible, could be immensely healing. But societies bear a responsibility to make certain things palpable for coming generations. Their distance in time may otherwise contribute to indifference — or worse, a susceptibility to repeat that marred history. This is why archival memorials like the ones at Auschwitz are so important, and why some have worried about fading knowledge of the Holocaust as the last survivors pass away.

But in general run of everyday life, being able to engage in constructive forgetting can be beneficial.

It allows us to shape and re-shape our understanding of who we are, where we’ve come from, and where we’re going. Insofar as our past is a mixed bag of pride and shame, elation and pain (and whose isn’t?), you could even say that this process is borderline redemptive.

But that becomes hard to accomplish if we lean more on archival rather than formative memory. As T. S. Eliot wrote in his Four Quartets,

“If all time is eternally present

All time is unredeemable.”

Expert creativity

One of the marks of expertise is an ability to make connections between diverse, sometimes radically different topics. An excellent book on educational psychology, How Learning Works, argues that “One important way experts’ and novices’ knowledge organizations differ is the number or density of connections among the concepts, facts, and skills they know.”

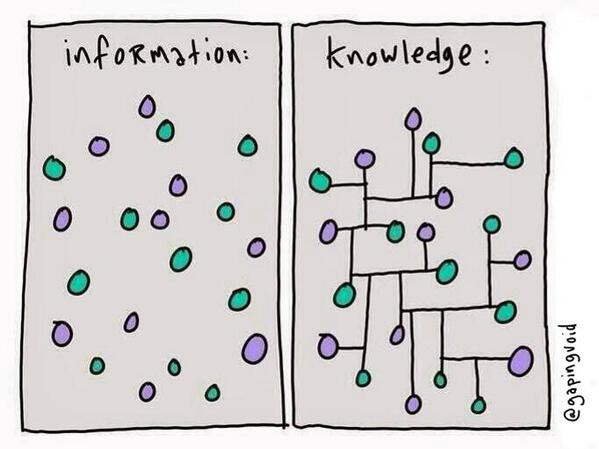

Hugh MacLeod, artistic director at Gapingvoid, has summed up this idea in a lucid image.

Drawing by Hugh MacLeod

The left hand image epitomizes the state of our minds when we’re first becoming acquainted with something. We may have memorized some details but cannot speak to how things fit together. We only attain the right hand image when the information has become a part of us as we literally rewire our brains.

We could see this as related to constructive forgetting. As we internalize things, their edges soften. Taxonomical distinctions between them remain abstractly valid, but are physically false, because everything we internalize belongs to the dense neural network that is our understanding. We may find ourselves prone to thinking and speaking in terms of analogies — new sorts of relations we have been able to perceive by bringing together previously unacquainted things.

This process conduces to creativity because new ideas are rarely born from thin air. Instead, they emerge from surprise unions that turn familiar ways of looking at the world on their head — what Maria Popova aptly calls “combinatorial creativity.”

You can get this on the Internet to some degree when vastly different materials are linked by hashtags or juxtaposed, one strangely after the other, in the results of a keyword search. But that merely sets the stage for creativity.

To realize the potential of such combinations requires the expertise of formative memory, because creativity doesn’t just combine things arbitrarily. It can tell a story about the relationship and why they belong together, as though they’ve been longing for just this moment of union.

Character

This takes the previous two benefits a step further. As I mentioned already, the consummation of formative memory isn’t cognitive recall (“I remember that…”) but embodied performance.

Edgar Degas, “Two Dancers on Stage.” 1877.

This is easy to appreciate with something like dancing. Suppose you’re learning Argentine tango and are still painfully awkward in your steps. (I’m really describing myself here.) It would do no good to consult Google every time you need to think of your next step, even if you had some kind of augmented reality available through your glasses. You might step correctly, but you would not be dancing. In an improvisational dance like tango, the “correct” step emerges from the intuitions you develop through practice, not a prescribed sequence.

When it comes to character, something similar is at work. As Aristotle pointed out long ago, character isn’t something we’re simply born with. It’s formed, like wet clay on a potter’s wheel, through habit.

“We are by nature equipped with the ability to receive [moral virtues], and habit brings this ability to completion…[We] become builders by building houses, and harpists by playing the harp. Similarly, we become just by the practice of just actions, self-controlled by exercising self-control, and courageous by performing acts of courage…In a word, characteristics develop from corresponding activities.” (Nicomachean Ethics 1103a25–1103b)

Becoming a person of character is a lot like becoming a decent dancer. Both require practice. Usually a lot of it.

The habits we develop through practice express a kind of formative memory, because past actions chart a course for future actions and even set them in motion. The more we do certain things, the more we’re likely to do them in the future. And as habits form, we’re likely to need less deliberate thought or reminders to carry through on our intentions. We simply recognize that a situation calls for a certain response, and engage accordingly. That’s constructive forgetting in action.

At their best, though, these habits aren’t simply automatic repetitions of things we’ve done in the past. That would be less a habit than a reflex. Instead, habits that we develop through formative memory can help us to adapt to unanticipated situations through our ability to make connections with familiar situations from the past. That’s expert creativity.

As with the other two benefits of formative memory, we simply can’t develop our characters in the right ways if we’re fixated on using technology as our vehicle of memory. The kinds of memory it supports are just different.

A crucial thing to recognize about habit and character formation is that they’re constantly in development regardless of our focus. It’s just a question of how they’re developing. The deeper worry that animates Carr and other critics, I think, is that using technology as a prosthetic mind, a substitute for personal memory, shapes character in negative ways — transforming us into people who are fragmented, absent, impatient, and shallow.

I’ll leave it to you to consider whether they’re right. But even if this fixation would not have downright negative effects, it could dampen the positive developments that would otherwise be possible when being more proactive in our development.

Toward formative memory

The paths to cultivating formative memory are numerous and varied, but one overarching point is certain: there is no substitute for attention and personal engagement in the passing moments of our lives.

In many moments, we face a simple choice. We can attempt to capture it with archival memory — perhaps holding up our phone to record a video or punching a note into a cloud-based app. Or we can hold our attention on the moment, unmediated and diversion-free.

As I mentioned already, we often resort to archival memory when a moment seems significant, too special to allow its destruction by the fires of time. But hazarding that loss by giving our undivided attention allows the moment itself — not a representation of the moment — to impress itself on us deeply. By doing that, we ourselves become the vehicle of its preservation, not some external thing prone to obsolescence.

Relying on archival memory takes the burden off our attention, since we expect that we’ll always be able to reference the moment later. But formative memory involves taking responsibility — concentrating in the ways we need to be, on the things we need to be, at the times we need to be — not just in one isolated moment of self-satisfied triumph, but over and over again.

Relying on archival memory also can divert us from the ways in which we’re constantly being formed anyway, even amid our diversions. But the responsibility we take in formative memory commends a next step in this recognition. We might consider taking a more active role in that process, imagining the sort of person we’d hope to become and taking steps to ensure that our formation stays true to that vision. That may impact the books and other media, the people, and the situations you immerse yourself in, just to name a few examples.

Paul Klee, “Angelus Novus.” The philosopher Walter Benjamin considered this painting an emblem of redemption by and from history.

Running through all of these thoughts on formative memory, you may have noticed, is a bright, optimistic thread. The past for anyone is rarely just sweetness and light, and if it’s been formative, it just as likely has been scarring as edifying. But tethers to the past can make for excellent slings. Fragments of past things may hint of possibilities yet unrealized, urging us ever onward.

To the extent that we can pull ourselves away from merely archival thinking about memory, we may find ourselves freed to riff on the jagged edges of our past, incorporating them into something new and unanticipated, something we can inhabit as the kind of person we’d hope to be.

Eliot, I think, expressed this possibility best, and I’ll leave you with a few more lines:

“This is the use of memory:

For liberation — not less of love but of expanding

Of love beyond desire, and so liberation

From the future as well as the past…

History may be servitude,

History may be freedom. See, now they vanish,

The faces and places, with the self which, as it could, loved them,

To become renewed, transfigured, in another pattern.”

All Rights Reserved for Austin Campbell