The origins of musical theatre performance can be traced back as early as ancient Greece and the European renaissance. They were predominantly either dramatic retellings of religious texts or farces made to mock popular operas of the time. Overall, integrating music into theatre was not taken very seriously throughout history; musicals weren’t thought of as a serious art form, their only purpose was light hearted comedy. It wasn’t until productions such as Oklahoma! (1943) and West Side Story (1957) came along that they were able to defy previous musical conventions. They had cohesive plots, character development, and were rich with social thought. They laid the groundwork for other talented writers to produce shows of their own: Jerry Block’s The Fiddler on the Roof (1964), Andrew Lloyd Webber’s The Phantom of the Opera (1986), as well as Claude-Michel Schönberg’s Les Misérables (1985) and Miss Saigon (1989), to name a few. The late twentieth century was a golden age for the musical theatre world. The advent of the heavily pop-influenced “mega-musical” was born, and theatre took its place in popular media. However, its newfound presence came at a cost: Musical theatre was, and still is, becoming nothing more than a spectacle in the dominant culture. This is no more apparent than its abrupt transition from the stage and onto film.

Source: variety.com

The death of the Hollywood musical has more in common with Marvel’s Avengers: Infinity War than it does, say, the recent Mama Mia! Here We Go Again. There was a time when musicals were the must-see films in town, rather than the endless sequels and remakes of superhero movies that we have today. These Broadway-style musicals were the backbone of cinema in the mid-twentieth century. Ever since the advent of sound in film, musicals quickly became a popular staple on the big screen. They were the natural development of the stage musical, as they allowed for more abundant scenery and locations that hadn’t been possible in the theatre. MGM Studios hired Arthur Freed in 1939, who produced films synonymous with the classical golden age of musicals, such as On The Town (1949), Singing in the Rain (1952), and An American in Paris (1951). In the 1950’s and 60’s, studios kept the momentum going for their extravagant movie musicals through the “roadshow”. Roadshows were essentially a gimmick used to promote film-viewings as more prestigious and fanciful than they really were. Before they were released to the wider public, studios would take these films on the road and show them to a more affluent audience. “[Audiences would] be insulted if you didn’t charge premium prices and make it a little hard to see. This way they [wouldn’t] have to rub elbows with the gum chewers” (Kennedy, 5). The musical films that earned top dollar were almost always road-showed before release. They were presented with overtures, entr’actes, and exit music to mimic, as best they could, a night out at “the theatre.” To buy a ticket to a roadshow was to build prestige around the movie; making it feel more like a Broadway show than a celluloid picture. Essentially, it was an overpriced ploy to get butts into seats. They were effective in getting acclaim for the show through word-of-mouth, which made them a risky but profitable marketing strategy. Hollywood was beginning to play a dangerous game, however. Roadshows were their answer to solving the threat of television, but their solution that had worked for decades was beginning to fall flat. Studios threw roadshows together as a marketing method for any and every movie being produced. “Should these gigantic investments achieve the desired outcome, Hollywood may well have found the definitive and triumphant answer to the threat of television. Should they encounter defeat the whole face of the film industry may be drastically changed. Will the public pay the higher prices made necessary by these colossal expenditures? Is there an audience sufficiently large to permit these pictures to emerge without a loss?” (5).

Source: theoscarbuzz.blogspot.com

To make matters worse, a collection of movies were released during this time that completely bombed, most infamously being that of 20th Century Fox’s Cleopatra (1963). They were bombs of such immense proportion that they nearly bankrupt entire studios. These premiers were incredible expenditures, as fewer and fewer audiences came to see them and ticket prices continued to soar. Studios began to realize that the concept of the roadshow wasn’t worth the time and investment anymore. Additionally, excitement for movie musicals were as bland as the stories in them. To quote Leslie Caron, one of the last studio musical stars of the 1950’s, “I could feel musicals were dying, because there wasn’t a renewal of stories and styles and they kept repeating the same plot. Finally the musical died because it was too expensive” (5). The musical film and film industry at large seemed to be reaching its breaking point.

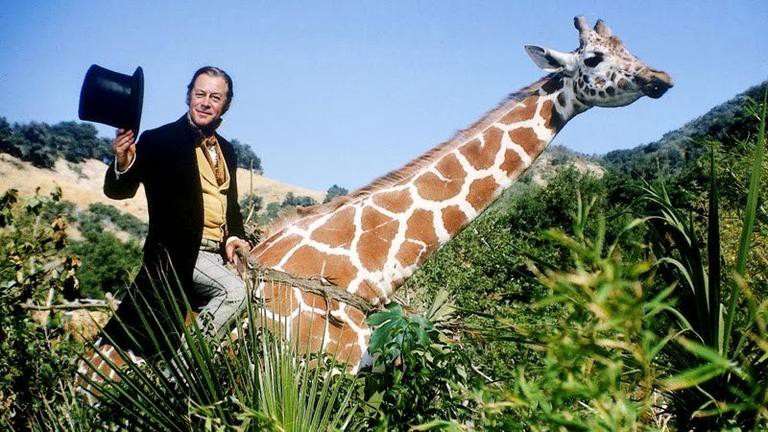

By 1963, the number of movie musicals in production, as well as all other American films, reached an all-time low. Audiences were exhausted by uninventive plots and aging actors, which crippled creativity in most major studios. The future of musical film didn’t appear all-too-bright, that was, until Walt Disney walked onto the scene with Mary Poppins (1964). The film launched Julie Andrew’s career and revived the Hollywood musical just as it seemed to be lying on its deathbed. Soon after, Warner Brother’s My Fair Lady (1964) was released, along with everyone’s favorite, The Sound of Music (1965). The film produced record box office numbers as a roadshow feature, and essentially reversed the disaster 20th Century Fox had with Cleopatra. It remains as the third-highest-grossing film of all time in the U.S. Just as it seemed that the era of big-time musical movies was on its way out, three massively successful films come out one after the next that revived the genre altogether. The roadshow was still very much on its way out, yet studios decided to milk it for all its worth. Camelot (1967) and Doctor Dolittle (1967) are complete disasters following the success of films such as The Sound of Music. They were ridiculed for their sense of traditionalism and sentimentality. Additionally, they were incredibly over budget, due to Camelot’s over-attention to historical accuracy and Doctor Dolittle’s cost for animal upkeep.

Source: chicagotribune.com

Roughly 2 million dollars were allotted for over 1,200 animals that were on set, including two giraffes, one of which died after they tried to get actor Rex Harrison to ride it. The other giraffe created a three-day production delay after it “stepped on its own genitalia”. In one instance, ducks were placed on a lake for a scene, but apparently had forgotten how to swim and began to drown. It was a mess, to say the least. Producer Robert Zanuck best sums up the fiasco in saying, “You look back now and ask, how could you have been so stupid? Doctor Dolittle was conceived in a period of euphoria. We were all riding a musical wave that we didn’t realize was going to come crashing down on the beach all at once. Sure, there were probably signs and warnings out there, but you’re already so committed financially and emotionally that it is very hard to pull the plug on these big undertakings” (Kennedy, 100). As if the film did not have enough problems already, it also came under allegations of being racist. Critics claimed that Dolittle is the embodiment and the “personification of the great white father nobly bearing the white man’s burden,” and that African characters in the film “emerge as quaint, comic, childlike figures with simple minds and ridiculous customs and funny-sounding names” (100). The animals were even portrayed to be superior to the Africans. Times were changing, and these films were remnants of an era that was already on its way out.

All it took was for one last monstrously expensive musical to put the final nail in the coffin, which came in the form of Hello, Dolly! (1969). The Broadway show was incredibly popular, winning a record-breaking 10 Tony Awards and having run for six years at the time. It seemed like only a natural choice for a film adaptation. The movie came with its own list of controversies, however, that are almost more entertaining than the film itself. Barbara Streisand was cast for the role of Dolly, essentially stealing it from Carol Channing who had shaped the character in the musical version. The studio wanted a younger, more attractive actress to play the main role which sparked the feud between Streisand and Channing. Moreover, the relevancy of the film was also taken into question. The story follows the romantic exploits of well-to-do turn-of-the-century white New Yorkers, which did not relate to most audiences. The main issue is that studios were adapting dated stage shows into dated full-length features. By the time they were released they were already unmemorable.

Following the trend of the death of Hollywood musicals, there are a few exceptions to this that make the cut: Fiddler on the Roof (1971) and Cabaret (1972). Fiddler did not feature any bankrupting stars or sets, and Cabaret was far more experimental and counterculture than its predecessors. Its director Bob Fosse “made a musical for people who hated musicals” (Kennedy, 232). These were the types of musicals that were new and exciting that Hollywood moguls were ignoring in the hopes of playing it safe. It was an endless cycle of studios trying to stay relevant within the culture, all the while choosing not to produce musical films that were actually interesting to audiences. They wanted trends to stay the same so they could be the ones to usher in new ones. This is still incredibly relevant today, what with films such as Venom trying to capitalize on trends that died years ago. Mama Mia! Here We Go Again is different in that there was a genuine desire for it. There were plenty of wine moms in the world who longed for a sequel.

Trends continued to change and studios quickly followed suit. Musicals and films that were being released slowly began to resemble stories that were more relevant to audiences. Although, it was rare for them to achieve the “realness” and “truth” that they were aiming for. Shoot forward to 1994 and Jonathan Larson produces Rent. The musical follows a group of struggling artists trying to make by in the East Village of New York, meanwhile under the threat of HIV/AIDS. It was one of the first musicals to have any substantial LGBTQ representation and was a large step in humanizing the community to the public. It followed the countercultural trend, which ultimately led to much of its downfalls as a “voice of a generation”. It attempted to tackle the pandemic that was the AIDS crisis in the 1980’s, but failed to do so in a lot of ways and leaves a feeling of dissatisfaction in retrospect.

Source: lebeauleblog.com

Rent tried to capture the emotions of those who were left behind by the system and attempted to make a grand statement about society. Although, it ended up being muddled by romanticism in the guise of a revolution. There is little in the musical that challenges the structures and the individuals that created so many problems for the people depicted in the show. The characters openly harass those who are wealthy and in positions of power, but those individuals are almost always showed to be calm and sympathetic. The show avoids alienating those who are wealthy because the main audience buying tickets are those wealthy white people. In effect, it disenfranchises the real people who struggled during the AIDS crisis. Millions of people died and the “voice of a generation” musical they got was Rent, which essentially capitalized on their tragedy. Rent isn’t unique in this aspect, however. Musicals such as Hair (1967), Jesus Christ Superstar (1971), and Les Misérables (1985) were each decade-defining and simultaneously profited off of those who were left out of the system.

The time when musical theatre was new and exciting has all but passed; it has outlived its fullest potential. It didn’t take long for its spot on center-stage to be overthrown by rock and roll and the likes. Once an exciting scene for aspiring composers and artists, it now takes its niche in American culture as merely a tourist attraction. “The simple economics of being a composer of new/serious/art/sound art music are pretty brutal… [without] large-scale institutional support, new music as we know it wouldn’t exist in this country… it’s a truism to say that keeping everyone just about the breadline is a good way of ensuring that the niche remains a niche” (Service, 7). Now that musical theatre has outlived its period of pure and raw creativity, it has succumb to the power of capitalism and the dominant culture; its survival is dependent on its economic success. Shows only get bigger and flashier to sell more tickets. Even Lin-Manuel Miranda’s Hamilton isn’t revolutionary enough to change the industry forever. It still remains within the confines of a traditional musical structure, and owes its overwhelming success to its endorsement by the public sphere. “It is difficult [for music to be politically motivating] because of the paradox of capitalist appropriation — if a work circulates enough to have a wide political impact, then it has likely been appropriated by capitalism” (Hawk, 34). Similarly, in an attempt to create something new and politically provocative, Miranda’s work has been appropriated to no end by a musical theatre world that is predominantly filled with white people. Everyone wants to take a piece of the national sensation that is Hamilton, without any consideration for the author’s original intent; he didn’t cast men and women of color to play historic white figures for no reason. However, the irony is that the only people who can actually afford to see the show are predominantly white people. This conundrum is hard to escape for any musical theatre composer or director. Theatre is so ingrained in the dominant white culture, and it would take many, many years to further integrate it into other ethnic subcultures (not to say that it doesn’t exist within them, just that they hold minimal influence). Stephen Sondheim himself contends that the culture surrounding theatre has faded away over the course of his career, and that for those outside of the theatre world, seeing plays and participating in the dominant culture, it is merely “a spectacular musical you see once a year, a stage version of a movie. It has nothing to do with theater at all. It has to do with seeing what is familiar. We live in a recycled culture” (Rich). Sondheim’s crippling nostalgia aside, if there is any hope for the theatre world to evolve, it is important to see it from a new perspective.

Theatre should intend to be enjoyed by a wider audience, not just by the actors and critics existing within the musical theatre world. Perhaps waking up to that reality opens up some room for new ideas and concepts to formulate, and for revolutionaries within the culture to awaken and surmount the work of their predecessors. As long as there is still a passion for theatre, it will still exist as an art form. It will take constant attention to see if the content is relevant and truthful in its storytelling, and not purely about making a profit.

All Rights Reserved for Grant Hoover