When Apple revealed macOS Catalina at WWDC this month, one related announcement drew considerable interest from Mac users and developers alike: a new way to turn iPad apps into fully native Mac apps.

Dubbed Project Catalyst, it promised to increase the number of quality native apps on the Mac platform by leveraging developers’ existing work in the arguably more robust iOS (and now, iPadOS) app ecosystem. But it does raise questions: what does this mean for Mac users’ future experiences? Will this change the type of software made for Macs? Is Apple’s ecosystem a mobile-first one?Advertisement

Then there are developer concerns: is Catalyst just a stepping stone to SwiftUI? What challenges can devs expect when adapting their iPad apps for the Mac?

Ars spoke with key members of the Apple team responsible for developing and promoting Project Catalyst at WWDC, as well as with a handful of app developers who have already made Mac apps this way. We asked them about how Catalyst works, what the future of Apple software looks like, and what users can expect.

The Mac is a popular platform among developers, creatives, and beyond. But while the iPhone and iPad App Store have thrived as one of the industry’s most vibrant software ecosystems, the Mac App Store hasn’t gained the same level of traction or significance, despite the presence of powerful applications that are not available on mobile.

Apple seeks to funnel some of its success with the iOS App Store over to macOS using Catalyst. We’ll go over how developers use what Apple has built step-by-step, as well as what challenges they faced. And we’ll share Apple’s answers to our questions about how the company plans to maintain a high standard of quality for Mac apps as an influx of mobile-derived apps hits the platform, what Apple’s long-term plans for cross-platform apps across the entire ecosystem look like, and more.

Before we get started, here’s a list of the Apple representatives and third-party app developers we spoke with for this deep dive:

- Todd Benjamin, Apple’s senior director of marketing for macOS

- Ali Ozer, Apple’s Cocoa engineering manager who worked on the Catalyst project

- Shaan Pruden, Apple’s senior director of partner management and developer relations

- Manu Ruiz, an engine software engineer at Gameloft who worked on bringing the iPad game Asphalt 9: Legends from iPad to Mac

- Alex Urbano, a graphics engineer at Gameloft who also worked on the Mac version of Asphalt 9: Legends

- Rich Shimano, an iOS developer at TripIt, a travel app that was brought natively to the Mac using Catalyst

- Nolan O’Brien, Twitter’s senior staff software engineer who used Catalyst to bring Twitter back to the Mac

An introduction to Project Catalyst

Bloomberg reported way back in December 2017 that Apple was working on a project that would make developing apps for both macOS and iOS side-by-side easier. We learned at WWDC this year that one major component to that push is called Project Catalyst, which enables porting iPad apps to the Mac relatively quickly.

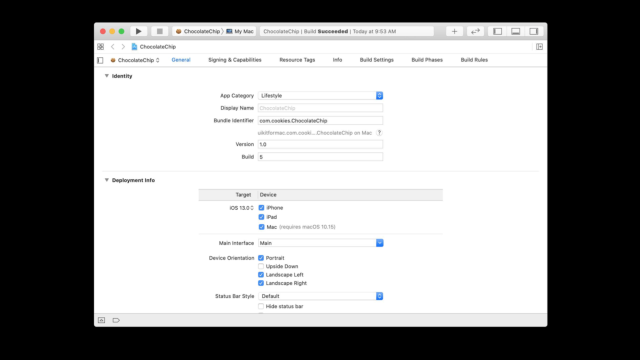

App developers can start doing this now with the beta version of Xcode, the development environment Apple maintains for making apps for its various platforms. To much fanfare on the WWDC stage, Apple claimed developers simply need to open their iPad app project in Xcode and click a single check box to be able to build a Mac app. Of course, it won’t always be quite that simple—but it’s closer than you might think.

Apple’s new framework, Project Catalyst, will help iOS developers translate existing mobile apps into macOS apps.

- Apple’s new framework, Project Catalyst, will help iOS developers translate existing mobile apps into macOS apps.

- Much of Project Catalyst’s work begins in Xcode.

- Apple also introduced a new cross-platform UI framework called SwiftUI.

The idea is to handle some of the difficult aspects of porting a mobile app to the desktop—like moving from a touch-based interface to a mouse-pointer-based one—automatically and quickly so developers can jump right into adding desktop-specific features where desired.

Here’s what Apple’s developer site says about it:

Mac app runs natively, utilizing the same frameworks, resources, and runtime environment as apps built just for Mac. Fundamental Mac desktop and windowing features are added, and touch controls are adapted to the keyboard and mouse. Custom UI elements that you created with your code come across as-is. You can then continue to implement features in Xcode with UIKit APIs to make sure your app looks great and works seamlessly.

Note that this is not emulation we’re talking about; Apple instead sought to make it possible to build native applications for both the Mac and the iPad from the same Xcode project.

Apple dedicated multiple sessions at WWDC to educating developers on its efforts and what it considers to be the best practices for adapting iPad apps for the desktop. Todd Benjamin, senior director of marketing for macOS, explained to Ars why Apple has decided to make this a priority now:

We’re at a stage at this point now where developers have fully developed iPad apps, and there’s a great opportunity to take the work that they’ve done there, which not only leverages what they had done on iOS, but also takes advantage of screen space and some things that we can leverage nicely as we bring them over to the Mac.

Senior director of partner management and developer relations lead Shaan Pruden added:

[Developers’] customers had been asking them for a Mac version because they have a big install base on the iPad, and they just didn’t feel like they had the wherewithal to spin up a whole other development team and do a port.

And why go from iPad to Mac instead of the other way around? “We have millions of apps out there for the iPad,” Apple Cocoa engineering manager Ali Ozer, who worked directly on making Catalyst a reality, told Ars. “So there’s a direction which makes more sense, at least when it comes to enabling developers.”

Critically, bringing iPhone apps over to macOS is not what Catalyst does—they have to be iPad apps. This might seem surprising: the iPhone has one of the most robust software ecosystems in the world, whereas the iPad is mostly a subset of that. There are some iPad apps that aren’t on the iPhone, yes, but there are countless iPhone apps that aren’t on the iPad.

Benjamin said Apple made that decision because it’s a more natural transition to bring an app from the iPad over to the desktop than it is to adapt an iPhone app over:

Just design-wise, the difference between an iPad app and an iPhone app is that the iPad app has gone through a design iteration to take advantage of more screen space. And as you bring that app over to the Mac… you have something that’s designed around that space that you can work with and that you can start from.

Ozer noted that the move is also about pre-empting user concerns about mobile ports spilling into the desktop even though the ports aren’t appropriate for the platform. “This is one way of making developers aware that an iPhone app in its current form might not be the right design,” he said.

How it works

Many of the frameworks developers use to create apps for the iPad and the Mac are similar. Part of what Apple did here was bridge the differences that previously existed between the iPad and Mac versions of shared development frameworks. But the biggest gap is that between the UI frameworks.

Developers build user interfaces and functionality of iPad apps using the UIKit framework. Meanwhile, the Mac has a framework called AppKit that does many of the same things. Previously, Mac apps could not run apps made using UIKit, and iOS devices could not run apps made using AppKit. Even if a developer could reuse some pieces of their iPad apps when building Mac versions, doing so took a considerable amount of additional work.

The Catalyst process starts, as Apple is very keen to point out, by clicking a single checkbox.

- AppleThe Catalyst process starts, as Apple is very keen to point out, by clicking a single checkbox.

- AppleThe heart of Catalyst is the effort to make UIKit join these other frameworks as one native to the Mac. (These are slides from Apple’s WWDC sessions.)

- AppleAn illustrative example of the macOS and iOS stacks side-by-side. Apple could already run the iOS stack on the right on the Mac in Xcode’s simulator. But the simulator wasn’t designed or optimized to integrate with the rest of the Mac UX.

- AppleThis is what the stack looks like after Catalyst.

- AppleHere’s a list of deprecated frameworks Apple recommends leaving behind when bringing iPad apps to the Mac. While some deprecated frameworks may work on the iPad for a while yet, developers can’t count on them working on the Mac.

- AppleDevelopers can use conditionals to run (or not run) specific code depending on the device.

When viewing their iPad project in Xcode, a developer can check a box to select the Mac as a supported device. After that’s done, Xcode makes the following changes to the project, according to Apple’s documentation:

- Adds a bundle identifier for the Mac version of your app.

- Adds the App Sandbox Entitlement to your project. Xcode includes this entitlement in the Mac version of your app, but not in the iOS version.

- Adds My Mac to the list of destinations that you can choose when running your app from Xcode.

- Excludes incompatible frameworks, app extensions, and other embedded content.

Barring any errors, the developer should then be able to deploy a basic version of their app for the Mac. The following Mac-specific features should automatically be part of the new Mac version, Apple says:

- A default menu bar for your app.

- Support for trackpad, mouse, and keyboard input.

- Support for window resizing and full-screen display.

- Mac-style scroll bars.

- Copy-and-paste support.

- Drag-and-drop support.

- Support for system Touch Bar controls.

From this point, the developer can add menu-bar items, apply translucency to the primary view controller, display and populate a preferences menu, add hover events, and so on.

Some frameworks are available on one platform but not another—for example, ARKit is not available on the Mac, so a developer porting an app that uses ARKit to deliver augmented reality experiences will want to consider that. In some cases, code pertaining to features and frameworks not present on the target device will automatically not be used.

In other instances, developers can, of course, use conditional logic in their code to deliver different experiences and functionality based on which device the software is running on. Apple, however, intended for that approach to be reserved for cases where functionality is simply not available on a certain device but is desired on another.

“We’d like them to use conditionals as little as possible because, you know, conditionals are different code paths that you have to worry about,” explained Ozer. “And I think that the things we’ve tied to conditionals are APIs and features that are really very much Mac-only.”

Apple says that many of the developers building the first third-party Catalyst apps managed to get an acceptable build running on the Mac within 24 hours. But each faced some challenges unique to each app.

Developers on their experiences so far

Apple brought in a handful of developers to build the first third-party apps using Catalyst. Their apps were shown at WWDC, and to get the fullest possible perspective, Ars spoke with developers behind three different apps that were part of Apple’s Catalyst presentation. The developers we talked to successfully brought the iPad versions of Twitter, TripIt, and Asphalt 9: Legends to the Mac.

Twitter discontinued support for its Mac app in 2016. While some third-party Twitter apps are still available for macOS, the company went on to treat the Web as the primary way for Mac owners to use the social media platform.

When detailing Catalyst on-stage at WWDC this year, Apple revealed that Twitter will return to the Mac. Twitter developers were invited by Apple to build a new native Mac Twitter app by bringing the well-supported iPad app over via Catalyst.

“We realized that we were unable to provide the same level of support to all of the Twitter clients, which ended up hurting some of them, including Twitter for Mac,” Twitter engineer Nolan O’Brien told us of the initial decision to end support.

“What Project Catalyst specifically offers is the ability to use our existing codebase, meaning that we don’t have to maintain separate code or a separate team to support Twitter for Mac,” he went on to say.

O’Brien said it was relatively easy to get going with the new app: “The surprising thing that got us excited about Project Catalyst was how much of our existing iOS codebase was able to just work.”

The transfer wasn’t quite as simple as checking a checkbox in Xcode to deliver something that felt like a fully native Mac experience, though.

“Multiple-window support isn’t simple, and it is different than windows with AppKit,” he explained. “Beyond that, multiple windows means each window is running simultaneously and can break expectations on being confined to one presented view controller at a time; they also need to deal with resizing which can run up against assumptions we’ve made when building for an iPad.”

“Not having any events for when the app is backgrounded or minimized” demanded some additional thought and work. “This affects things like database persistence, suspending active operations that don’t need to be running and generally maintaining good hygiene for the app’s lifetime,” O’Brien said.

Finally, the deprecation of OpenGL was a pain point. “One of the challenges we faced was that we had many years of built up infrastructure and features using OpenGL: blurs, photo filters, graphical touches and flair,” O’Brien said. “Since OpenGL was deprecated at WWDC last June, we focused this past year on deprecating it on our end as well.”

The deprecation of OpenGL has created a few headaches for Apple developers, and we’ll be going deep into that in another article in the future. Nevertheless, these challenges were minimal compared to trying to support the Mac without this easy crossover from the iPad. “This will elevate Twitter for Mac support to the same level as iPhone, iPad, and iPod,” according to O’Brien.

Asphalt 9: Legends

You’d think porting a graphics-intensive 3D game like Asphalt 9: Legends would present significant additional hurdles. But that’s not exactly how Gameloft Barcelona graphics engineer Alex Urbano and engine software engineer Manu Ruiz described it.”The process was fairly simple—open the current iOS project on the new Xcode, mark the new macOS target option, and compile,” Ruiz said. “Obviously, it didn’t work on the first try as some of our libraries were not supported on non-mobile devices—motion controls for example—and some third-party libraries weren’t prepared for macOS and x86-64 platforms. That said, after refactoring some of the code, we managed to compile and run the entire Asphalt codebase in roughly 24 hours.”

On the graphics side, Urbano told us:

It was pretty straightforward. We had to adapt some shaders precision to make them work properly at higher resolutions in high-end Macs and in order to improve performance even more. We changed slightly how Metal buffer management worked. This wasn’t strictly necessary, but it allowed us to implement some effects not present in any other platform while preserving our 60fps target at native resolution.

We were curious about how laborious optimizing performance for the new platform would be with something this GPU-dependent. To that question, Urbano said:

Desktop and mobile GPUs are radically different, but generally speaking, any optimization done for the latter—avoiding overdraw, limiting blending objects as much as possible, optimizing geometry while keeping a close eye on the amount of drawcalls per frame—is going to help greatly on the new platform.

One could use the extra power of [the Mac] to cover the difference in resolution and to add extra effects. In the case of Asphalt 9: Legends, we enabled self-shadows for cars, temporal super sampling, higher-quality motion blur, and SSR.

In the end, porting to macOS using Catalyst was trivial enough since Asphalt 9: Legends is already built to handle big differences in resolution, aspect ratios, platform APIs in general, and device capabilities. This is one of the main advantages of developing your own tech, as it gives you the flexibility to quickly adapt to new platforms.

Ruiz added that one of the key challenges was actually UI-related. “Adapting your UI to work on bigger displays can be quite a challenge, and what works on mobile doesn’t necessarily need to be done on desktop,” he explained.

TripIt

If you really want to get into the nitty-gritty, iOS developer Rich Shimano sent Ars an email with a detailed list of each step that was taken to bring travel planning app TripIt from the iPad to the Mac. Here’s the whole thing:

1. Getting our current iPad app to build in Xcode, which required just a few iterations of identifying and then removing various dependencies on unsupported resources such as phone-call-specific frameworks or third-party iOS SDKs not yet built to support MacOS.

- Click the “Checkbox,” as described at WWDC, to enable Mac support from our existing iOS project, and let Xcode perform automatic linking of relevant frameworks and set up a unique bundle identifier for the new Mac app. This process of “flipping a switch and then excluding unneeded items” was much simpler and less error-prone than creating a new macOS target from scratch and pulling in all necessary frameworks and source files.

- Remove and replace a few sprinklings of long-deprecated Apple frameworks and APIs, such as MessageUI and UIWebView, which are not supported by Catalyst.

- Remove dependencies on unsupported mobile-specific frameworks.

- Remove dependencies on unsupported third-party frameworks (for now) such as Crashlytics, Facebook sign-in, or Google Maps. (We hope that many of these will become available when iOS 13 officially launches.) Xcode’s project-management user interface has been upgraded to allow easy inclusion/exclusion of frameworks, source files, and other resources in iOS+macOS, iOS-only, and macOS-only builds.

- Wrap any remaining references to excluded resources in our source code with new UIKitForMac availability specifiers in Swift and Objective-C.

2. Running through all user flows and data-syncing scenarios, and shutting down unsupported or unavailable features.

- Our mobile apps offer account sign ups through Google and Facebook, but since those are not yet supported, we simply disabled buttons providing those flows.

- Likewise, we have an airport gate and terminal feature relying on a third-party framework to provide maps. We needed to disable UI elements that describe and trigger that feature, and we had to physically exclude code that pulls data from that feature.

- Fortunately, all of our networking, keychain, and Core Data persistence code worked as expected without change, so not having to rewrite that code was a huge time savings.

3. Tailoring the UI to improve user efficiency in the Mac’s multi-window point-and-click environment.

- Modify the information architecture of our tab-bar-based mobile app to use the sidebar area for core in-app navigation.

- Move action affordances from content areas into a global toolbar at the top of the screen.

- Introduce some new split views to utilize screen space more efficiently and eliminate the need to navigate through a series of screens.

- Leverage a new hover state in list views to indicate a selection affordance.

- Introduce context menus and keyboard shortcuts, which will also be available to users with external keyboards on an iPad. This will also allow users with limited mobility to navigate screens and access actions with a switch device using a minimal number of gestures, which adds yet another dimension to our current efforts to make our apps universally accessible.

- Catalog and provide access to all user actions from the main menu bar.

- Pursue new avenues to leverage iPad drag and drop capabilities within the app thanks to new split views and multi-window use cases.

As for challenges, Shimano said the most significant were “old codebases relying on deprecated Apple frameworks and APIs and older versions of Swift,” which “may need major rewrites with more current APIs.” Also, “iPad apps that are not multitasking-friendly with flexible layouts may need major rewrites relying more on Auto Layout in order to render appropriately on desktop windows that will vary greatly in size and aspect ratio, even in a single user session.”

Apple on making sure Mac apps stay desktop-class

As Apple and its partner developers talk up how straightforward it is to bring iPad apps to macOS with Catalyst, user concerns linger about the future quality of apps on the Mac.Apple’s first apps made within what became Project Catalyst actually shipped with macOS 10.14 Mojave, Apple’s annual major macOS update last year. They included Voice Memos, News, Home, and Stocks. While they got the job done, computing enthusiasts lamented that they felt and acted like lackluster mobile ports.

Mac power users are concerned that an easy path to bring iPad apps to the Mac will disincentivize developers from delivering the powerful, deep, and full-featured desktop applications those users have enjoyed on the Mac in the past. Partly, this is because mobile apps tend to be focused on narrower tasks, and they often don’t carry feature sets as robust as those found in good desktop apps. It’s also partially that, regardless of Catalyst, UIKit and Catalyst do not give Mac developers the full breadth of features and frameworks they’d have access to if they used AppKit to build a native Mac app from the ground up.

The Apple team members we spoke to didn’t share the concern, of course. For one thing, UIKit does offer developers some access to AppKit, according to Ozer. “When you bring your UIKit app over to the Mac, we do leverage AppKit a great deal, when you’re using toolbars or Touch Bars, for instance, or menus—these are all AppKit,” he said. “So the developer doesn’t have to use AppKit directly, but they are using AppKit in their UIKit apps in that context.”

Still, Apple agreed that AppKit is the way to go for broad and deep Mac apps like those used by creative professionals and power users. Pruden said she believes Catalyst is about offering developers options but that teams creating powerful desktop apps will know whether it’s suitable for their products or not.

“Good developers will know their audience and their users and what they’re going to want,” she said. “This just opens the door for lots of people to consider coming that wouldn’t have even thought about it before. And I think that’s more the target for this particular technology as opposed to someone who has a very complicated, big, heavy-lifting kind of creative app.”

Focused apps vs. broad apps

To Pruden’s point, Benjamin believes there are fundamentally multiple types of apps, and they’re not mutually exclusive with one another on a platform. And this is key to understanding Apple’s approach, here. He said:

I think apps on the Mac have always been these large and complex and highly capable apps that are very broad. And I think apps on iOS by nature are a little bit more focused. They’re highly designed. They’re very much considered in what they do and how they do it. And I think that’s changed how people look at apps, right?

He continued:

Now people know what those things are, and they would love to have those kinds of simple and accessible experiences on the desktop as well. And while the Web can actually do that, an app is a more focused thing… now you’re used to using that experience that’s relatively new on your phone and on your iPad. Why can’t that same experience translate over to the Mac?

And it’s not just a matter of those focused-used apps coming to desktop: Apple wants broadly powerful apps to head to the iPad as well. When Ars reviewed the iPad Pro last year, we were impressed by the tablet’s performance, which rivaled many professional laptops, including Apple’s own MacBook Pro in some tasks. The strength to do heavy lifting was there, but at the same time, we lamented that the software wasn’t. Most creative apps on the iPad Pro are stripped-down versions of their desktop counterparts.

“I think maybe the two worlds might be getting closer and closer together,” said Pruden. “So I don’t know that, if you went from the iPad that you’d be missing a whole lot.”

You’d be missing a lot today, to be clear. But that could quickly become not-the-case with upcoming releases like Adobe’s full-featured Photoshop for iPad Pro.

And Apple also announced at WWDC that it is essentially branching a new, iPad-specific iPadOS out from iOS—exactly what we called for in our iPad Pro review, in fact—which means adding much more powerful multitasking features, among other things that would encourage power users to adopt Apple’s tablet as a day-to-day workhorse. Apple hopes the third-party software will follow to match the iPad Pro’s performance and iPadOS’ flexibility.

“The court of public opinion”

As it always does, Apple has provided developers with a number of guidelines and best practices for them to follow when developing apps for its platforms. “There are some sort of basic human interface guidelines you need to follow, and obviously the default behavior that we’re going to give them will follow the human interface guidelines,” Pruden explained.

That means things like translucency, robust status bar and touch-bar support, appropriately designed multi-window workflows, and so on. So what if developers are satisfied to release their apps without implementing these things well? And what happens if developers release an iPad port when their users really wanted or needed an app built for the desktop from the ground up, with all that AppKit and related APIs have to offer?

“Then we come down to customers’ reaction and ratings and all of that kind of stuff,” Pruden answered. “Which hopefully will drive the right behavior for a developer, which is to do the work and do it right and don’t be lazy.”

Here’s how Benjamin put it:

Developers have already survived the court of public opinion on the highly competitive iOS App Store, right? There’s a lot of choice there, and they haven’t succeeded there by doing the least amount of work possible…

If they were to do a port that is—that people look at and go, “I don’t actually think this is such a great app,” it’s going to show on the ratings. It’s going to show in the reviews and the feedback, and that’s kind of how the process works. And if [developers] do that, they’re just leaving an opening for someone to do a better job.

Pruden also argued that the fact that it’s so easy to get a basically functional version of an iPad app running on macOS quickly encourages quality, not the other way around.

“You get something up and running, like, the first day, and it feels like a Mac app. But because it was so easy, then they’re like, ‘Oh, well then, now I can actually add all the extra bells and whistles because they’ve provided this kind of stuff.'”

Why make a native Mac app when there’s a Web app?

While Apple and Microsoft are expending considerable effort to attract developers to make native apps for their desktop operating systems, Google is taking a different tack based on very different financial incentives.Google’s emerging Chromebook category is essentially dumb terminals for the 21st century, designed from the ground up for a Web-browsing experience and to use Web-based apps. But the Mac has a long tradition of focusing on native apps. Why should Apple devs continue that here by porting over software from the iPad instead of just letting Mac users access their Web apps in Safari or Chrome?

Benjamin believes it’s about performance. “The performance of that app as a native app versus a Web experience is dramatically different,” he said. Additionally, “there’s another benefit, which is that the user gets a consistent experience when they move between devices.”

A developer perspective on Web vs. native

When we asked TripIt’s Shimano for the developer perspective on this, he shared similar reasons for going native rather than Web on the Mac, citing the “quick and responsive interactions of a native app.” He agreed with the second point too: “building and supporting native Mac apps directly from the iPad versions makes it easier to maintain feature parity among platforms and to establish a stronger brand identity since the codebase and UI are constrained to be tightly coupled.”

Also, “a native Mac app can provide our users with offline access to securely review and edit travel data while performing other offline tasks on their MacBooks,” Shimano said.

It remains to be seen how many developers will take this extra step for the user experience, though. Some will likely see their Web apps as adequate for desktop users and stop there, despite Apple’s efforts to entice them to go native with Catalyst if they have iPad apps.

Developers on when they’d consider AppKit instead

We asked the developers whether (and under what circumstances) they would have considered forgoing Catalyst to build Mac apps from the ground up with AppKit.

“We would have probably considered it if we had to take advantage of any specific hardware feature only present in Mac devices,” Gameloft’s Alex Urbano said. “However, if that is not a requirement, Catalyst is a perfectly valid option to have our game in a whole new platform with very little development effort.”

For Rich Shimano’s (TripIt) part, AppKit wasn’t considered. Catalyst was the clear choice because all the business logic from the iPad ported over to the Mac app. That allowed TripIt to focus on user experience that’s optimized for the Mac. “If we were to research any alternatives, it would be because this alternative would allow us to create both an app for macOS as well as an app that runs on Windows and/or Chromebook,” he added.

macOS and iOS: The chicken and the egg

Given that iOS and iPadOS seem to be at the heart of this new paradigm, we asked Apple whether it considers iOS (and iPadOS) the lead development platform for its ecosystem. Does Apple expect developers to support mobile first and foremost, with other platforms coming downstream from that?

Initially, Pruden answered by focusing on the fact that different devices and operating systems lend themselves toward different use cases, so no one platform is going to be more essential than the other in every developer’s case:

We love all our children equally. Speaking from a developer relations point of view, they’re such different use cases, and depending on what company you’re talking to, Watch might be their lead thing… We try and, like, tune them for what their use cases are that are completely different. And depending on what company you’re with, you’re going to have a tendency to lean into one of them more than others.

“From a volume point of view, obviously there are probably more iPhone apps than anything else,” Pruden went on to say. “But I don’t think we think about it that way in terms of how priorities go into where features happen and how much effort we put into it and where we’re supporting developers next.”

And then there’s SwiftUI. While Catalyst is intended to help developers bring pre-existing iPad apps over to the Mac, Apple suggested that it sees SwiftUI as the place to start for new, cross-platform projects moving forward. In that eventuality, it wouldn’t be so much about developing for iOS or iPadOS first and macOS later as it would be about developing for all appropriate native Apple platforms in tandem.

The path to SwiftUI, according to Apple and developers

Catalyst wasn’t the only big announcement for developers at WWDC. Apple’s SwiftUI is a framework designed to “declare the user interface and behavior for your app on every platform” using Xcode and Apple’s Swift programming language.

From Apple’s developer support documentation:

SwiftUI provides views, controls, and layout structures for declaring your app’s user interface. The framework provides event handlers for delivering taps, gestures, and other types of input to your app, and tools to manage the flow of data from your app’s models down to the views and controls that users will see and interact with.

Prominent developers on Twitter have speculated that SwiftUI is Apple’s desired final destination, with Catalyst being a stopgap before that eventuality. When asked whether that’s the case, Pruden said:

I see the analogy to how Swift worked right from the beginning. You didn’t have to start with a new project and have everything in Swift… and people sort of migrated over time.

We worked with a lot of developers where all their new development was in Swift, but 60% of the code was still the stuff they had from before and they just added things on. And if they do a brand new project from the ground up, it’ll be all Swift. And I have a feeling that’s probably what’s going to happen with SwiftUI as well, that new things that they’re developing they’ll use the newest tool for.

Benjamin said something similar, noting that SwiftUI and Catalyst are designed to live side-by-side. “These tools can be used together… they’re not mutually exclusive,” he said. “Every developer is going to be at a different point in their app development with whatever titles they have.”

Apple’s aforementioned support documentation states that “you can integrate SwiftUI views with objects from the UIKit, AppKit, and WatchKit frameworks to take further advantage of platform-specific functionality.”

While it’s difficult to quantify exactly how quickly Swift has been adopted, the pattern so far does appear to match what Pruden described. Engineer and macOS/iOS developer Andrew Madsen recently came up with a clever way to estimate how widely used Swift is in apps already in Apple’s App Store.

Here’s his top-level explanation:

I downloaded the top 110 free apps on the app store on January 15, 2019. I decrypted them, then wrote a script that does some simple analysis of their contents to determine whether or not they’re using Swift, and roughly how much of the app is written in Swift…

In order for an app to be considered to “use Swift”, it must include libswiftCore.dylib in its Frameworks folder, and it must have at least one Objective-C compatible Swift class in the main executable. Some apps don’t use Swift in the main executable but include dynamically linked frameworks that use Swift.

Madsen found that 42 percent of those apps used Swift, though that percentage rose to 57 percent when he eliminated games. In fact, none of the games in the list were using Swift, as they were mostly probably written with cross-platform tools like Unity. And, of course, many of the apps that do use Swift use it in tandem with Objective-C code, similar to what Pruden described.”In the past three years, Swift has gone from being used in a small minority of the most popular apps to being used in roughly half of them, which is a huge increase and shows how well Apple has done with introducing a new language,” he concluded.

That bodes well for SwiftUI—and is evidence that Pruden’s take on where SwiftUI can go and how it can relate to Catalyst and other existing Apple development frameworks.

As for developers, Shimano said TripIt already has “some key motivators to adopt SwiftUI, independent of the Mac app.” Namely, it would allow the TripIt team to share common code with its watchOS app to improve feature parity, and it would “simplify and reduce the amount of code needed to display rapidly changing travel data such as flight delays and gate changes.”

“However, we are experimenting with specific desktop views that could potentially find their way back to the iPad and even the iPhone,” he added. “By writing those with SwiftUI within a single codebase, we should be able to bring enhancements to our iPad and iPhone apps quickly and easily via Catalyst with little to no rework.”

For Twitter’s part, O’Brien said, “Right now, we are focused on moving our very large codebase over with many legacy UIKit interfaces to the Mac. Project Catalyst is a good solution for us at this time.” But he did say that Twitter’s team is “very excited for the possibilities that SwiftUI brings with it” and that the company is “open to adopting SwiftUI for new features in the future.”

Three ways to make Mac apps

To sum some of this up, there are now three different approaches to developing native Mac apps using Apple’s own tools and frameworks:

- Build an iOS/iPadOS app using UIKit, then turn it into a macOS app using Project Catalyst. According to Apple, this is intended for focused-use apps that have so far been more common on mobile but not on desktop.

- Build the app for the ground up for macOS using AppKit and associated frameworks and APIs, tapping into the full power of the platform. This is appropriate for traditional, heavy duty, Mac-specific apps, Apple says.

- Build the app for multiple Apple platforms from the ground up using SwiftUI, which plays nicely with the other existent frameworks. This is what Apple expects developers to do for multi-platform apps in the future.

Some Mac users have felt that Apple has treated iOS as the star of the show lately, thus relegating the Mac to an understudy role. But for iOS, iPadOS, watchOS, and tvOS to succeed, the Mac has to succeed, too. Catalyst is an effort to bolster the Mac while keeping it tied closely to the company’s mobile platforms. It remains to be seen exactly how this will play out in the long run; a lot of stars will have to align for the optimal outcome Apple, developers, and users are hoping for.

If you look at the marketing for Apple products, you can learn plenty about who they’re intended for. Today, most Macs are marketed primarily to creative professionals of various types—from writers to graphic designers to video editors to developers to 3D animators—a shift from casting a wider net with the Mac in the past, for better or for worse. It would make sense then to see the Mac as the platform for creators, and iOS as the platform for consumers—by definition, the latter would be much larger. But the mobile platforms also couldn’t survive in the long run if the Mac, with Xcode for developing apps, didn’t thrive for at least some key target users.

So which comes first at Apple: the chicken or the egg? The Mac or mobile? As the adage suggests, both and neither.

But boy, wouldn’t both Apple and Mac users like it if some of that iOS software support came to the Mac, but with the added bells and whistles that make a good desktop app? Whether that happens will depend not just on developer adoption, but also on how Apple listens and responds to feedback from developers as it builds upon Catalyst, and for some new applications, SwiftUI.

Apple CEO Tim Cook previously assured both users and developers that Apple is committed to the Mac and iOS/iPadOS as truly distinct platforms. That’s still very much the case. But Apple, its users, and its developer community are entering uncharted territory nonetheless—those platforms will soon be even more closely linked than before. Dialogue between Apple and developers (and users, too) will determine how beneficial that will be.

All Rights Reserved for Samuel Axon